This, my latest book, was published in Germany

and the U.S. in late 2012, in Britain in January 2013, and 16 other translations have appeared or are pending.

This is also my most personal book. It grew out of my experiences for the last 50 years in New Guinea and neighboring islands, where I study birds but am almost constantly with New Guineans and spend much time talking to them. Until recently, New Guineans were living traditionally, with little or no influence from industrial Western societies – using stone tools, lacking matches and steel tools and writing and manufactured clothing, still practicing tribal warfare, divided into a thousand tribes speaking a thousand different languages (yes, different languages, not just dialects of a few languages), and without centralized government even within a tribe. When I first went to New Guinea in 1964, I was struck by how different from Americans and Europeans New Guineans seemed. As I got to know them better, and as I found that we laughed and cried and were frightened at the same things, I came to

think, “We’re basically all the same.” Then, as I spent time with them and came to know them still better, I realized that there actually are big differences in basic aspects of life, such as friendship, attitudes towards danger, how New Guineans treat their parents and their children, how they select their spouses, and how they interact with each other.

An Agta woman, from the mountain forest of Luzon Island in the Philippines. Photo credit: Jacob Maentz/jacobimages.com

That confusing mixture of similarities and differences is part of what has made it fascinating for me to spend so much time living with New Guineans. New Guinea is a vivid place, for many reasons: the beauty and great variety of its jungles and its birds; the great variety of its peoples, their lifestyles, and their languages; and the immediacy of interpersonal relations in New Guinea. Those relations are face-to-face, full-attention, undistracted by cell phones and texting. People are with each other and talking almost constantly during their waking hours. That style of relating is unlike the intermittent personal contacts of us Americans, who spend much of our time alone and silent at a computer or reading, and much of whose “talking” is indirect, out of sight, and mediated by a handheld electronic device. In traditional New Guinea there is no passive entertainment: no TV, radio, or movies; the entertainment consists of other people themselves. Being in New Guinea is for me like seeing an otherwise gray world briefly in bright colors.

New Guineans exemplify so-called traditional societies. That term is shorthand for small-scale societies consisting of a few dozen to a few hundred people, in which everyone knows everyone else and their relationships, strangers are rare and assumed to be dangerous, and centralized state government and writing are absent. All societies in world history were like that until the rise of the first state governments in the Fertile Crescent a little more than 5,000 years ago. Traditional small-scale societies still occupied much of the world five centuries ago, before Europeans started on their world-wide expansion of colonization and conquest. A century ago, there were still millions of people living outside state control and without knowledge of the remote outside world. Today, the few remaining uncontacted tribes are confined to areas of New Guinea and the Amazon, and they at least know of the outside world through airplanes flying overhead. But even within our modern state societies, many features of our traditional lifestyle persist, for instance in rural areas of the U.S. and other industrialized populous nations. That’s why I chose as my book title The World until Yesterday. Measured by the time scale of the 6,000,000-year history of the human evolutionary line, traditional societies really did blanket the world until almost yesterday.

My readers will find traditional peoples fascinating to read about, for the same reasons that I’ve found them fascinating to live with. We can understand them, and we can communicate with them, but they are still different from us in many ways. Besides that motive of fascination, our other motive for wanting to know about them is that we can learn things from them that may be useful for our own lives.

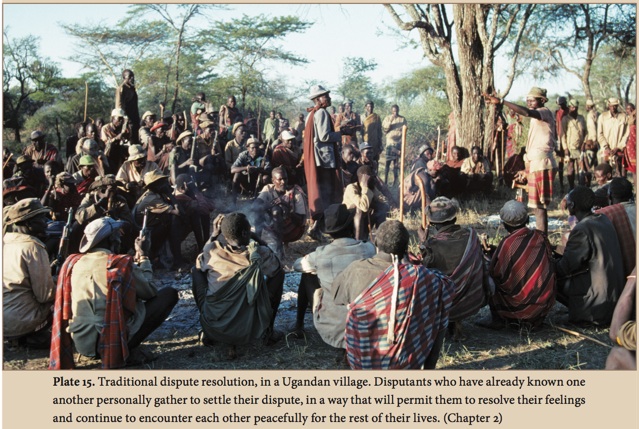

Image from The World Until Yesterday. Photo credit: Eye Ubiquitous/SuperStock.

Yet the attitudes of us Westerners towards traditional peoples swing between two equally unrealistic extremes. One view is that they are primitive brutish barbarians who should either be exterminated or else brought into the modern world as quickly as possible. The opposite view is the romanticized notion that they are happy, noble, peaceful, wise stewards of their environments, compared to whom we Westerners are bad. Neither of those two extreme views can withstand scrutiny. Traditional peoples do have many practices that dismay us and that cause misery for the traditional people themselves, such as strangling widows, abandoning or killing old people, and being trapped in endless cycles of warfare. They also have many admirable practices from which we can learn. In short, they are mosaics of happy and unhappy features, like us and all other peoples.

Traditional societies are far more diverse than are large modern societies with state governments, because all large societies with state governments have to converge on certain features in order to persist. We think of American, Japanese, Israeli, and German societies as being very different from each other. However, the differences between them are actually minor compared to the differences among traditional societies, which constitute thousands of different experiments in how to organize a human society. We citizens of modern states could never carry out those experiments on ourselves now. But the experiments have already been run for thousands of years by traditional societies, and we can learn from the outcomes.

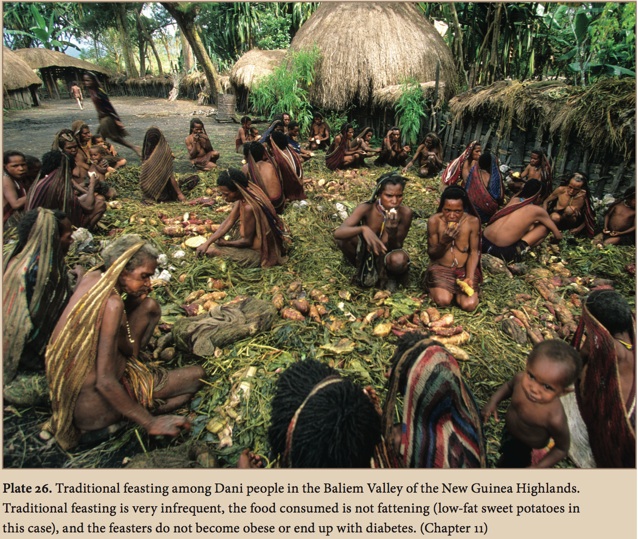

Image from The World Until Yesterday. Photo credit: Bruno Zanzottera/Parallelozero

Among the features of traditional societies that

we are likely to admire and want to adopt for ourselves is, most obviously, their freedom from diabetes, stroke, heart disease, and many cancers: the non-communicable diseases that will kill most of us Westerners. Subtler features that we may admire, when we learn about them, are traditional peoples’ ways of bringing up their children to be self-confident, socially skilled, and autonomous; the ways in which they have often provided satisfying lives for their elderly, a disaster area of modern American society; their ways settling disputes so as to provide emotional reconciliation and restoration of prior relationships; and their ways of thinking clearly about dangers. Those features have influenced me strongly in my own daily life and in my life choices.

Of course, to provide a full account of traditional

Traditional toys: Mozambique boys with toy cars they have made themselves, thereby learning how axles and other car components are designed. Traditional toys are few, simple, made by the child or its parents, and thus educational. Photo credit: Afonso Santos

societies would require a book at least 3,000 pages long, which no one would read or buy. Hence from the whole range of traditional societies and their features, my book stresses studies, by other scholars, of 39 traditional societies around the world on all continents. I illustrate their conclusions by anecdotes drawn from my own experiences in New Guinea. Even for these 39 societies and for the societies of my New Guinea friends, I select only certain features for discussion: dividing up space, settling disputes, warfare, bringing up children, treating old people, dangers, religion, languages, and health.

I hope that my individual readers, and our society as a whole, will come to share my fascination with traditional societies, will enjoy reading about them, and possibly will selectively adopt some things from the huge range of traditional human experience. Readers can find out more from my publisher’s website, and of course from my book itself.