About Me

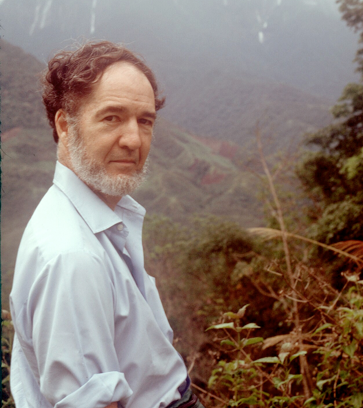

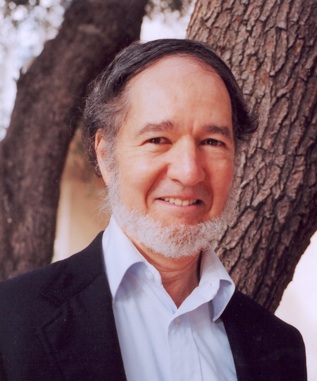

I divide my professional time between four areas: teaching geography to UCLA undergraduates; doing field research on the birds of New Guinea and other Southwest Pacific islands; writing books about human societies, aimed at the broad public; and promoting sustainable environmental policies, as a director of the international environmental organizations World Wildlife Fund and Conservation International. I formerly also pursued a separate career of laboratory research in membrane physiology and biophysics at UCLA Medical School. My non-professional activities include being with my wife and children and friends, bird-watching around my house in Los Angeles, playing piano and chamber music, and reading and speaking other languages.

What do I do?

How I Came to My Mix of Interests

I was born and grew up in Boston. My father was a pediatrician who trained medical students and physicians and was known for his research on blood diseases of children. My mother was a concert pianist, school teacher, and linguist. From my father I acquired my interest in science. From my mother I learned to love reading and writing, and I began piano lessons at age 6. I have a younger sister to whom I was constantly trying to explain things, and that may have contributed to my lifelong interest in trying to help other people and myself to understand the world.

Being born in 1937 meant that I grew up during World War Two. It may seem silly to imagine that an American who was only 7 years old at the end of the war could have been influenced by World War Two at all. The fact is, though, that for those of us Americans who grew up then, the World War was ubiquitous, even for children. It formed our games and our fantasies. It was different from subsequent wars in that it was a simple, virtuous war against enemies whose leaders were indisputably evil. Unlike Vietnam and other recent American wars, there was no debate about World War Two in the United States after Pearl Harbor, even though it turned out to be a long, difficult, and dangerous war that lasted four years for Americans, six years for Europeans, and 14 years for Japanese and Chinese. Even to those of us who were still children when the concentration camps and the POW camps were liberated in 1945, the images of the skeleton-like survivors crowded at the camp fences waiting for food, and of the bulldozers pushing the bodies of the overwhelming numbers of dead prisoners into trenches to be burned, have remained with us for the rest of our lives.

I had the good fortune to attend for six years a wonderful small middle school and high school, Roxbury Latin School. We students had few choices or electives. All of us took Latin for five years. The other choices we faced were in sophomore year between Greek and biology, then in junior year between Greek and physics, and finally in senior year between Greek and contemporary events. I expected to become a doctor, like my father. Besides, I was interested in birds, hence in biology, and I also liked mathematics, all predisposing me towards science. Medicine was considered then to be the best training for a career of research in biology. Nevertheless, I decided to take the Greek electives rather than the science electives, because I expected to be doing science for the rest of my life, so I figured I might as well do something different and take Greek now. Also, I loved languages, and I had a great Latin and Greek teacher at Roxbury Latin School.

I have been learning languages ever since then. In my 60’s I learned my 12th, and what will probably be my last, language: Italian. Another subject that I learned to love from Roxbury Latin School was history. We had a great history teacher, and a fascination with history that he taught me has stayed with me. I also loved writing the weekly compositions that my mother corrected with me each week, and that love of writing stayed with me.

From Roxbury Latin I went on to Harvard College, where I began to do laboratory science research, but I took a minimum of science courses, again reasoning that I was going to be doing science for the rest of my life, so I might as well do something different now. I am glad that I made that choice: the college courses that have stuck most with me were a course in music composition that has increased my music appreciation ever since, courses in Russian and German, a course in oral epic poetry, and a course in the history of the American Revolution.

In my senior year of college, for the first time, I finally faced a difficult decision: should I really go to medical school, as I had been saying ever since I was a child, or should I instead get a Ph.D. to prepare myself for scientific research? It was a difficult decision, to imagine jettisoning the path on which I had been planning ever since I could remember. I didn’t make that decision until April of my senior year in college, after I had been admitted to medical school. In retrospect, it turned out that it was much better for me to get a Ph.D. than to go to medical school. Nevertheless, that decision with heavy consequences was a close call.

A Dani man, from the Baliem Valley of the New Guinea Highlands. Photo credit: Carlo Ottaviano Casana.

A summer trip to the big tropical island of New Guinea in 1964 launched me on a parallel second career of ecology and evolutionary biology, for which the birds of New Guinea and other Pacific islands furnish ideal study systems. New Guinea changed my life. It’s a very different place. It was an eye-opener that had a big effect on my outlook. I still go there; I will be going back soon for my 27th trip. New Guineans were then known as “primitive” people, meaning that traditionally they didn’t have metal tools but just stone tools, they didn’t have writing, they didn’t have kings or chiefs, and they had little in the way of clothing. That led me naively to expect them to be primitive in other ways as well. But I soon found out that they were instead very smart people. Why, then, didn’t they have writing or steel tools, when I the dope who couldn’t find his way or light a fire in the jungle did have writing and steel tools? That was a question that stayed in mind for a long time after my 1964 trip, and it finally resulted in my 1997 book Guns, Germs, and Steel to answer that question.

A traditional border between tribes, guarded by a Dani man on a watchtower, from the Baliem Valley of the New Guinea Highlands. Photo credit: Michael Clark Rockefeller.

I found that New Guinea is an unforgiving place if you make mistakes. In Boston, when I sprained my foot in Harvard Square, I phoned my physician father, and he took care of it. But if you sprain your foot in the New Guinea jungle, several days’ walk from the nearest airstrip, you're in deep trouble. You have to learn to be ultra-careful and to do whatever it takes not to sprain your foot. Hence one of the basic lessons of life that I learned from New Guinea is an attitude towards risks -- specifically, towards doing things that involve very low risks each time you do them, but that you're going to do hundreds or thousands of times. A "Eureka moment" came one afternoon when I picked a campsite in the jungle underneath a tall, dead tree. I was surprised how frightened the New Guineans with me were of sleeping under that dead tree that night. When they said that the tree might fall down, I answered, "Look, it's not going to fall down tonight." But after hearing stories of New Guineans killed by dead trees, and after hearing trees fall down in the jungle, I gradually realized that, if you're going to spend every night of your life in the jungle and you are not careful about dead trees, sooner or later that low-risk event of a dead tree falling on you will catch up with you. That lesson has made me much more sensitive about low-risk things that we do repeatedly - such as driving, climbing ladders, and walking on slippery surfaces.

Traditional trade: a canoe of New Guinea traders, carrying goods to be given to traditional trade partners in return for other goods. Photo credit: Peter Hallinan.

New Guinea also solved my career problems. I was able to develop two parallel careers, one in laboratory physiology, the other in evolutionary biology of New Guinea birds. I also had the good luck to get launched on a third career, that of writing, by the stroke of luck that a friend recommended me as a writer to Nature Magazine, which led to my writing for Discover Magazine, which led to my writing for Natural History Magazine, which led to the opportunity to write books for the general public. I gradually discovered that I was becoming more interested in people and in history, and that I was losing my interest in molecules and in molecular physiology.

With the birth of my twin sons in 1987, I came to realize that the state of the world in the mid-21st century was not just an academic topic about events to culminate at unreal dates long after my death, but would involve the conditions under which my sons will be living their adult lives. It was pointless for my wife and me to buy life insurance and draw up wills for the benefit of our sons, if we were simultaneously launching them into a world not worth living in. The changes that I had seen in New Guinea since I began to work there in 1964 boded ill for New Guinea birds, forests, and people. Those changes had already motivated me to devote much of my efforts in New Guinea to designing national park systems for the governments of Papua New Guinea, Indonesian New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands, surveying individual national parks, and joining the board of directors of World Wildlife Fund and then of Conservation International. Hence I eventually made a career switch, but it’s one that took a long time. It didn’t become completed until I reached age 65, when finally after 45 years I ended my career in laboratory science and began devoting myself half-time to geography and comparative environmental history, while carrying on my other half-time career in evolutionary biology.

Working in academia, and writing about geography and environmental history, are things that I love. It's not work: it’s fun. I happen to get paid for that fun, but if someone tomorrow gave me ten million dollars, I would continue my job as professor of geography at UCLA, because it's what I most enjoy. In retrospect, if I had known at Roxbury Latin School that I wanted to end up as a historian or geographer, I think I still would have followed the trajectory that I did. I would have prepared myself by studying biology, because from it I learned the comparative method, which is valuable both in field biology and in history. Languages are important too for understanding history. Understanding the New Guinean lifestyle has been important for me in understanding the lifestyles of peoples around the world, throughout history. And so what I actually did for 45 years, although it wasn't geography or history, was good unplanned preparation for my present career in geography and history. Already from Roxbury Latin School also came my love of writing. Writing lets me spend time reading up on all these interesting things, going to the effort of trying to understand them and to explain them to myself, and then explaining them to others in the same way in which I have tried to explain them to myself.

Ancient religion? The famous rock wall paintings deep inside France’s Lascaux cave still inspire awe in modern visitors. They suggest that human religion dates back at least to the Ice Age 15,000 years ago. Photo credit: Sisse Brimberg/National Geographic Stock.